The AI & Fed Bubble

Introduction

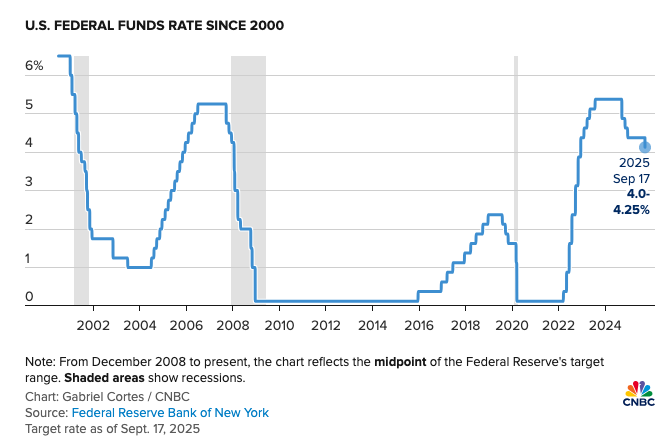

Stocks look untouchable again: fresh all-time highs, daily AI partnerships/deals, and a Federal Reserve that’s cutting rates while insisting inflation still hasn’t fully cooled. Yet the same forces that lifted this market — cheap money, optimism about AI, and a handful of mega-cap winners — now make it fragile. On September 17, 2025, the Fed cut rates by 0.25 percentage points and, in the statement, said inflation had “moved up and remains somewhat elevated.” According to the Fed’s published statement, that cut was framed as risk management given softening jobs data — not a “mission accomplished” on inflation.

At the same time, the Fed is still shrinking its balance sheet (that’s “QT”—quantitative tightening), just more slowly: in March the Fed said it would reduce the Treasury runoff cap to $5B/month starting April 1, 2025 (from $25B), while keeping MBS (mortgage-backed securities) runoff at $35B/month. According to the Fed’s Policy Normalization page and follow-up materials, that slower QT is still a drain on liquidity over time.

Overlay that with new tariffs that lift costs, record market concentration in a tiny group of AI-linked mega-caps, and increasingly self-feeding AI infrastructure deals (chipmakers ↔ AI labs ↔ cloud providers). You get a market that can fall 20%+ without a classic recession. How? Because when investors demand a higher return to own stocks — say, if the term premium (the extra yield for holding longer-term Treasuries) backs up — prices usually fall to make forward returns competitive again.

Quick definitions:

QT (Quantitative Tightening): the Fed lets bonds mature without replacing them — gradually removing cash from the system.

Term premium: extra yield investors want for holding long-term Treasuries; when it rises, stock valuations (P/Es) often fall.

Vendor financing: a seller helps fund a buyer’s purchases (great for sales optics in booms; dangerous if the buyer later pulls back), essentially allowing for deferred payment terms or a direct loan to facilitate the transaction.

Warrant: a long-dated option to buy a company’s stock at a preset price (used as an incentive in big supply deals).

Gross margin: revenue minus direct costs; a quick “is this business line actually profitable?” check.

Capex: capital expenditures — big, long-term investments (factories, data centers, chips).

The Fed Is Easing Into Sticky Inflation

The cut. On Sep 17, 2025, the FOMC cut by 25 bps and kept language that inflation “remains somewhat elevated.”According to the Fed’s statement (and mainstream recaps), the move aimed to cushion labor-market risks rather than celebrate victory on inflation.

QT is not done. In March, the Fed slowed QT but didn’t stop it: the Treasury runoff cap fell to $5B/month starting April 1, 2025, while the $35B/month MBS cap remained. According to the Fed’s policy page and its Balance Sheet Developments report, QT is still shrinking reserves in the background.

Why this matters: Cutting policy rates while QT still removes liquidity is a recipe for interest-rate volatility and a potentially higher term premium — and that pushes down equity multiples even if earnings don’t immediately fall. Fed officials are openly wrestling with AI’s effect on the real economy and rates: Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari said heavy AI data-center investment could push rates up even if the Fed cuts, since capital may flow away from housing into higher-return AI projects.

Translation: The discount rate that underpins stock valuations may rise even as policy rates fall, which is how you get multiple compression (lower P/Es) without a recession.

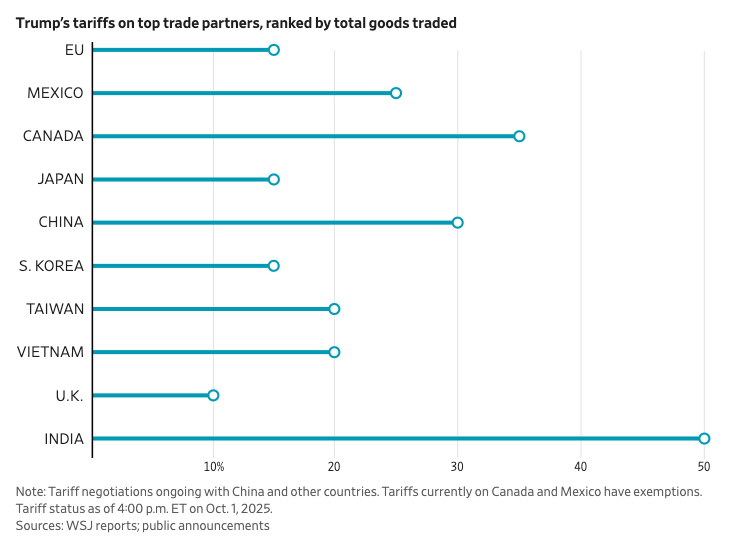

Tariffs Raise the Floor Under Inflation

Tariffs aren’t a one-off headline anymore — they’re baked into how global supply chains now operate. Across major trade routes, a shifting mix of duties, quotas, and rules-of-origin lifts the floor under costs. Companies either pass some of it through to customers or absorb it, so the first place the pain shows up is gross margin, not the CPI print. Avoiding tariff lines by rerouting production adds capex, paperwork, and slower clearance, which ties up working capital and raises ongoing operating costs.

For markets, that means a stickier inflation baseline and a tougher backdrop for valuations. If investors demand a higher term premium to own long Treasuries, equity multiples compress even if earnings hold steady. Operating leverage weakens, too: each incremental dollar of revenue drops less to profit, which matters most for import-heavy manufacturers, price-sensitive retailers, and capital-intensive buildouts like data centers and grid equipment. Watch the import-price index, PMI “prices paid,” and earnings calls that cite tariffs, rules-of-origin, or supply-chain rerouting as headwinds.

Why this matters: Tariffs act like a tax on traded goods. Some of that cost gets passed on to customers (inflation), and some gets eaten by companies (lower margins). If inflation stays sticky, the Fed faces a bad trade-off: cut more (risking re-acceleration) or pause (risking slower growth). Either path pressures valuations in a market already priced for perfection.

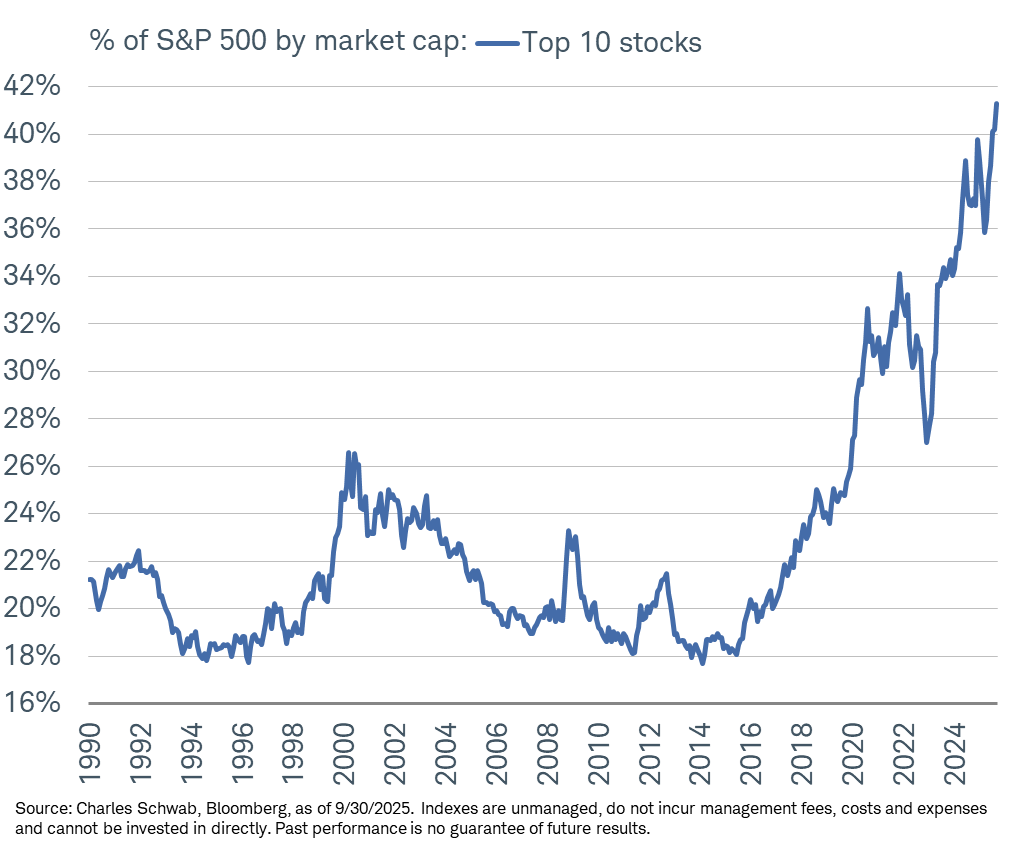

U.S. Equities are Extremely Concentrated

Narrow leadership. A handful of mega-caps now dominate index performance. Bloomberg recently put the top-10 S&P 500 weight near ~41%, close to record territory. Nvidia alone hovers around ~8%. That’s a lot of index tied to a very small group of names.

Leverage is high. FINRA margin debt (borrowing to buy stocks) hit a record ~$1.06T in August, up ~33% y/y, according to Advisor Perspectives’ read of FINRA data. Leverage doesn’t cause selloffs — but it accelerates them when crowded leaders stumble.

Valuations are stretched. The Shiller CAPE is hovering in the high-30s/low-40s — its highest zone since the dot-com era. High CAPE doesn’t time markets, but historically it reduces forward returns and raises sensitivity to rate and earnings shocks.

Bottom line: With leadership narrow, leverage high, and valuations rich, small disappointments (growth, rates, margins) can become big moves through the index.

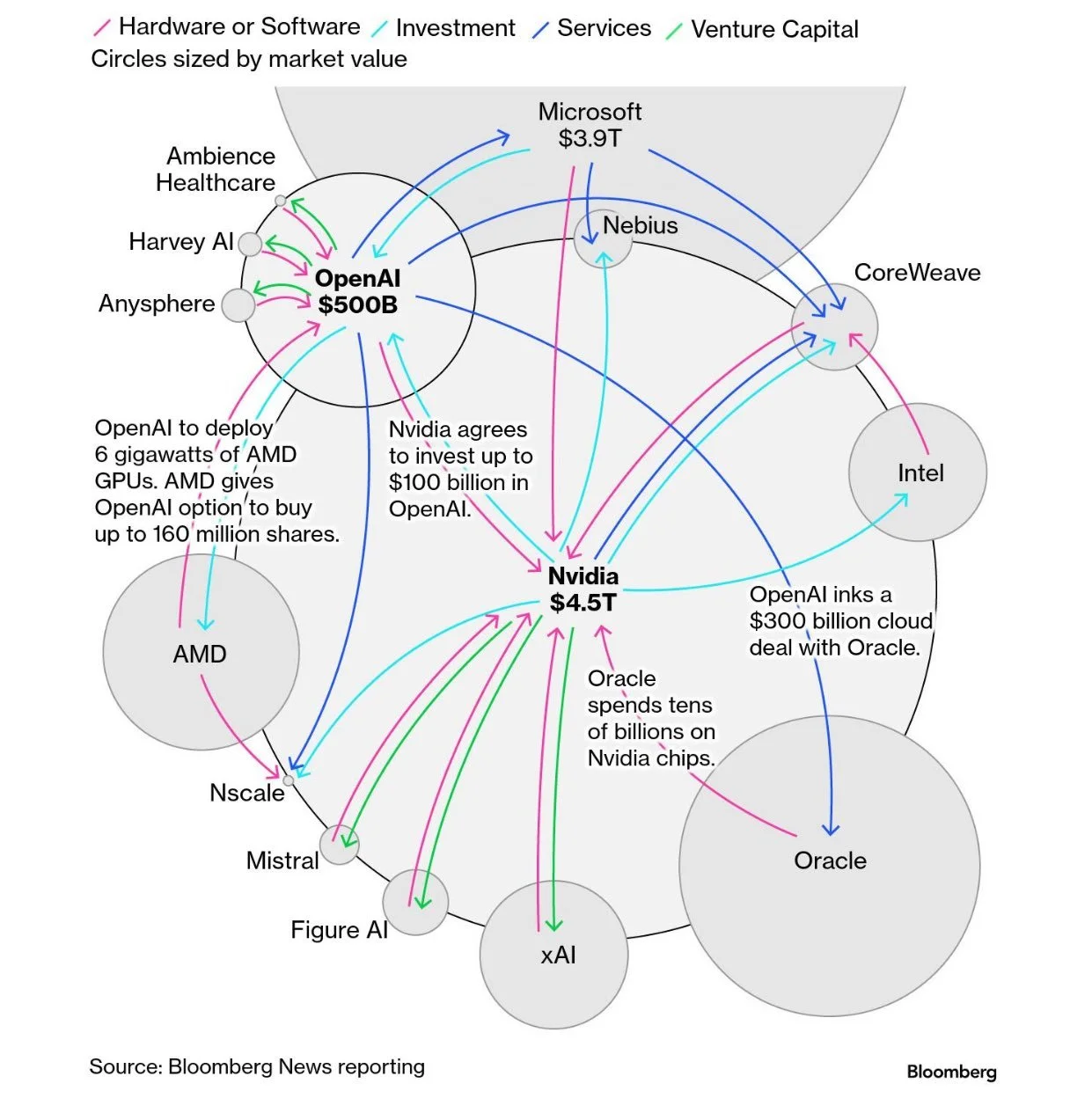

The AI Flywheel

NVIDIA ↔ OpenAI (compute) + Oracle (cloud): the “self-feeding” loop

Two weeks ago, NVIDIA and OpenAI announced a letter of intent (LOI) for a strategic partnership to deploy at least 10 gigawatts of NVIDIA systems (millions of GPUs) for OpenAI’s next-gen infrastructure, with the first 1 GW targeted for 2H 2026 on NVIDIA’s Vera Rubin platform. To support the buildout (including power and data-center capacity), NVIDIA says it intends to invest up to $100B in OpenAI, progressively as each GW comes online (emphasis on “intends” and “LOI”). That language comes directly from NVIDIA and OpenAI announcement pages and was echoed by Reuters.

Separately, OpenAI and Oracle announced 4.5 GW of additional U.S. capacity under “Stargate,” part of a multi-year $300B cloud/services framework, plus five new U.S. data-center sites, according to OpenAI and industry coverage.

Why this can become circular (in good times):

Supplier equity → buyer capex → supplier revenue. If NVIDIA helps fund OpenAI, and OpenAI buys NVIDIA systems — often hosted and monetized by Oracle — you get revenue optics on the supplier and cloud side that are partly funded by supplier equity. That’s not illegal; it’s reflexive. Reflexive loops supercharge upside — and can unwind quickly if funding tightens or unit economics underperform.

Today’s twist: Oracle’s GPU rentals look thin — or even loss-making in spots

Fresh reporting says Oracle’s margins on renting NVIDIA GPU capacity are much lower than many hoped — and that some deals even lost money. According to The Information, one quarter included roughly $900M in revenue but only $125M in gross profit (~14% margin), and some Blackwell rentals allegedly produced nearly $100M in losses. Follow-on summaries in WSJ and Investor’s Business Daily say the stock dipped on the news; bulls argue margins will improve with scale.

Why this matters: If the cloud partner at the center of AI infrastructure struggles to earn decent gross margins today, the whole buildout becomes more dependent on cheap equity and long-dated commitments to make the math work. That’s classic late-cycle risk — big promises supported by financing more than by current unit economics.

The AMD-OpenAI deal makes the flywheel bigger

This week, AMD and OpenAI announced a 6-gigawatt multi-year agreement to deploy AMD Instinct GPUs, with the first 1 GW (MI450) targeted for 2H 2026, according to AMD’s press release and OpenAI’s post. Reuters adds that OpenAI receives warrants to buy up to ~10% of AMD (up to 160M shares at $0.01 each) if AMD hits delivery/performance milestones — i.e., powerful equity-linked incentives that align supply with OpenAI’s ramp.

Stepping back, OpenAI’s aggregate compute plans across NVIDIA, AMD, Oracle and others are now frequently described as “$1 trillion” and 20+ GW over the next decade by major outlets. Even if that’s a round number and subject to financing and permitting realities, the scale is unprecedented versus OpenAI’s current revenue base.

Bottom line for investors:

When both leading GPU suppliers (NVIDIA and AMD) and a major cloud host (Oracle) tie their fortunes to the same demand curve from one buyer and its ecosystem, good news compounds—and so does the downside if unit economics disappoint.

The structure (supplier financing + customer warrants + long-dated cloud commitments) is pro-cyclical. It looks best when equity is strong and capital is cheap. If capital tightens, the loop can run backward: capex deferrals at the buyer/cloud; visibility downgrades at suppliers.

Power and Capacity are Real Constraints for AI

Even if the financing works, power and infrastructure are hard limits:

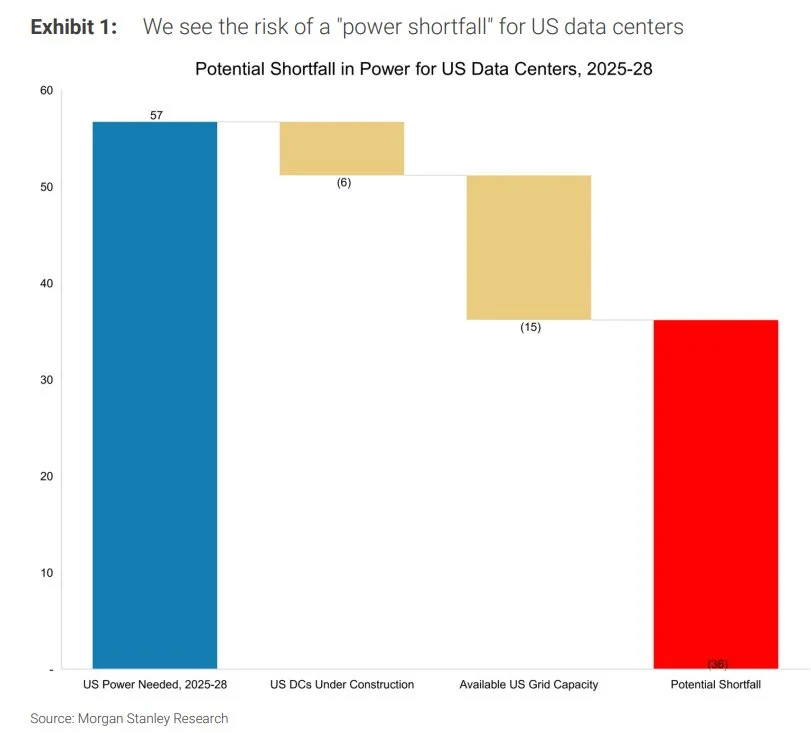

The EIA expects U.S. power demand to hit record highs in 2025–26 as data-center and AI loads surge.

The IEA and other research groups expect data-center electricity use to double globally by 2030, with AI the key driver. Some U.S. analyses put data centers at 6.7%–12% of U.S. electricity by 2030 (ranges vary).

PJM, the big Mid-Atlantic grid operator, is exploring cutting data centers first in emergencies to avoid wider blackouts; policy proposals and think-tank work in 2025 reflect mounting stress in Northern Virginia (“Data Center Alley”).

Industry groups estimate AI-specific load could rise from ~5 GW today to >50 GW by 2030 (EPRI/S&P Global). That’s like bolting on the demand of multiple states.

Why this matters for markets: Power constraints inject execution risk and timeline risk into AI capex. If facilities slip or power contracts get repriced higher, that can delay revenue recognition for suppliers and pressure cloud margins — yet another way the flywheel can miss aggressive expectations.

Why This Rhymes with Parts of the Dot-Com Bubble

In 1999–2001, equipment makers juiced sales by helping customers finance purchases (“vendor financing”). Sales looked great — until financing dried up and orders evaporated. Lucent is the textbook case: the SEC later said Lucent improperly recognized about $1.15B of revenue in fiscal 2000 (and overstated pre-tax income by ~16%), including deals with side agreements that undermined revenue recognition.

Today’s AI is not telecom, and I’m not alleging wrongdoing. The rhyme is the structure:

Suppliers funding or incentivizing demand (NVIDIA’s “intends to invest up to $100B”; AMD’s warrants to OpenAI).

Cloud partners reporting thin or negative early-stage margins on GPU rentals (Oracle’s ~14% gross margin quarter; alleged losses on Blackwell rentals).

Long-dated take-or-pay commitments and huge capex that depend on future monetization per dollar of compute.

If monetization lags, the loop can unwind fast: deferrals at the buyer/cloud → visibility cuts at suppliers → multiple compression in the same names that dominate the index.

Clear, Concrete Paths to a 20% (or worse) Drawdown

Policy slip → higher term premium → lower P/Es. The Fed cuts to support jobs while tariffs keep inflation sticky. Investors demand more yield for long bonds (term premium up). That lifts discount rates and pushes P/Es down 10–15% before earnings move—already halfway to −20%. (See the Fed’s own language and QT backdrop.)

AI profit scare. Cloud margins on GPU rentals disappoint (as today’s Oracle reporting implies), or a supplier/AI lab slips on shipments, power, or model timing. With leadership narrow, passive flows amplify the move — turning a sector wobble into an index event.

Funding/liquidity accident. Heavy Treasury supply meets ongoing QT; rate volatility spikes; multi-asset funds de-risk; equities gap down. (Fed: QT still on; lower Treasury runoff cap, but not zero.)

Vendor-financing loop runs backward. If AI revenue per dollar of compute lags: OpenAI/clouds defer capex; NVIDIA/AMD see order visibility fade; earnings and multiples compress at the top of the index. (Note the LOI nature of NVDA–OpenAI and warrant incentives in AMD–OpenAI.)

What Would Prove this Wrong (and keep the bull intact)?

Inflation glides toward ~2% even with tariffs, letting the Fed cut without term premia backing up. (That would keep discount rates tame.)

AI monetization (revenue and margins per dollar of compute) ramps faster than capex, and broadens beyond a handful of mega-caps—reducing concentration and improving cash conversion.

Power constraints ease (faster permitting, more generation/transmission), keeping deployment timelines intact. (EIA/IEA base-case projections would need to be comfortably absorbed.)

Treasury supply is absorbed smoothly, term premia fall, and the Fed ends QT earlier than planned.

Conclusion

We already had a market that was pricey (CAPE at 40), concentrated (top-10 weight near records), and levered (record margin debt). Layer on a Fed that’s cutting while saying inflation is still elevated, with QT still draining liquidity; tariffs that lift cost floors; and an AI build-out that’s increasingly self-funded by its winners — NVIDIA “intends to invest up to $100B” as part of a 10-GW LOI with OpenAI; AMD’s 6-GW deal comes with warrants; Oracle’s early GPU-rental margins look thin. According to the companies and major outlets, the scale (multi-GW) and financing (equity intentions, warrants, long-dated cloud contracts) are real — so are the execution and profitability risks.

None of this guarantees a crash. It simply lowers the bar for one. A small push — term premium up, an AI profit miss, a power/permits delay, or a funding wobble — can kick off multiple compression and forced selling, especially when the same names dominate both performance and passive flows. That’s a clear path to -20% even without a classic recession.

Standard note: Educational only — this isn’t investment advice. Do your own research and size risk appropriately.